My name is Ola Schubert, and for the past eight years I’ve been exploring the potential of acorns as a staple crop. Along the way, I’ve uncovered a remarkable body of knowledge—stretching back hundreds of thousands of years—carefully developed and passed down by Indigenous peoples around the world.

Humans have always had a close relationship with oak trees, largely because our survival has depended on them. The only thing standing between an acorn and a nourishing meal is knowledge—how to leach out the tannins, and how to prepare it. That’s a skill I’ve mastered, and it’s knowledge I’m passionate about sharing.

So far, I’ve created more than 50 different dishes using acorns as a base ingredient—and I’m just getting started. I believe acorns deserve a place alongside corn, rice, potatoes, and wheat as a key staple. In fact, acorns may be even more important: they grow on trees that live for centuries, produce oxygen, build soil, store carbon, prevent erosion, and support biodiversity.

It’s no wonder the oak has been revered throughout human history. We have thousands of years of food wisdom waiting to be rediscovered. I hope this site gives you both the inspiration and practical tools to begin your own journey with acorns.

The Historical Relationship Between Humans and Acorns as Food

The human relationship with acorns stretches back tens of thousands of years and across many regions of the world. With around 500 unique oak species spread throughout the temperate zones of the planet, acorns have long served as a source of nutrition for people. From the mountain ranges of North America and the Himalayas to the island worlds of Japan and Indonesia, from the northern forests of Canada and Sweden to the arid deserts of Morocco and Algeria—oak trees have adapted and thrived in vastly different environments.

Our story begins at a remarkable archaeological site in the Hula Valley in northern Israel, where discoveries reveal some of the earliest evidence of human acorn consumption. Here, at the dawn of humanity, charred remains bear witness to a time when acorns formed part of the prehistoric diet—a tradition that would shape cultures around the world.

Hula Valley, 780,000 Years Ago

The archaeological site in the Hula Valley, dated to around 780,000 years ago, offers invaluable insights into the diet and lifestyle of early hominins. The site, known as Gesher Benot Ya’aqov, lies on the shore of the ancient Lake Hula in the northern Jordan Rift Valley, part of the Dead Sea transform.

Twenty-six archaeological layers stretching 34 meters into the sediment show that Acheulean humans repeatedly camped along the lake for over 100,000 years. They made stone tools, hunted and butchered animals, gathered plants, and—perhaps most remarkably—controlled and used fire.

Findings suggest that acorns played a central role in their diet. Burned and charred acorns, especially from the Tabor oak (Quercus ithaburensis), have been found at the site, implying that they were not only collected but also processed—perhaps roasted—to make them more palatable and digestible. Alongside acorns, Atlantic pistachios (Pistacia atlantica) and wild almonds have also been identified, suggesting that nuts were a crucial part of the diet.

These discoveries paint a picture of a foraging culture in which people used a wide variety of local resources for survival. Here, on the shore of the ancient lake, our distant ancestors lived off what nature provided—and acorns were a vital part of that ancient nutritional web.

The Middle East and North Africa

In the Middle East and North Africa, acorns have been an important food source from prehistoric through historic times. The oak forests of Anatolia, the Levant, the Zagros Mountains, and North Africa have for thousands of years provided nourishment for both humans and animals.

Around the Mediterranean coast, several oak species grow, including holm oak (Quercus ilex), kermes oak (Quercus rotundifolia), prickly oak (Quercus coccifera), and cork oak (Quercus suber). Several of these oaks produce low-tannin acorns, making them edible with minimal processing.

In the Zagros Mountains, which span Iran and Iraq, archaeological sites such as the Shanidar Cave have shown that early humans—possibly late Neanderthals or early Homo sapiens—used acorns as food around 11,000 years ago. Additional evidence from Syria and southern Turkey further supports the idea that acorns were a staple in the region.

Even during the Epipaleolithic period (ca. 13,000–9,800 BCE), acorns played an important dietary role. At the Natufian settlement of Tell Abu Hureyra in modern-day Syria, mortars, bowls, and pestles have been found that were likely used to grind and store acorns. The Natufians were one of the first cultures to begin settling in one place for extended periods before the rise of agriculture. Acorns were part of their food system alongside wild cereals and legumes.

Further north, in the Anatolian part of the Fertile Crescent, lies the Neolithic settlement of Körtik Tepe by the Tigris River in present-day Turkey. Excavations show that around 10,000 BCE, its inhabitants relied on a wide range of natural resources. Rather than relying on cultivated grains, they appear to have lived on a rich and diverse diet including acorns, pistachios, hackberries, and almonds, along with easily accessible small animals such as turtles and fish. Finds from Körtik Tepe challenge the traditional notion that early sedentary societies depended solely on agriculture—instead, high-calorie wild plants like acorns may have supported permanent settlement.

In North Africa, acorns have long been used as food. During Algeria’s war of independence, a bread called khobz el ballout made from acorn flour was baked, though today it has largely been replaced by wheat. However, acorn flour couscous is experiencing a revival as a more climate-friendly and gluten-free alternative. In Morocco, acorns are also used to produce cooking oil.

Today, the tradition continues in regions such as Kurdistan, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, and North Africa. Acorns are roasted, ground into flour, and used to bake traditional breads like nani baru, nane belu, kalg, and pragi. For thousands of years, acorns have remained a resilient and nutritious resource—a bridge between prehistoric foragers and today’s traditional cuisines.

Asia

In East Asia—particularly in Korea, Japan, and parts of China—acorns have long been a staple food. Even today, acorn starch is used to make noodles and the jelly-like dish dotori-muk (acorn tofu) in Korea. The earliest signs of acorn consumption in Asia have been found in Fuyan Cave in China, where analysis of 80,000-year-old human teeth revealed traces of acorn starch.

During the Jōmon period in Japan (ca. 14,500–300 BCE), acorns were one of the most important food sources along with chestnuts, walnuts, and other nuts. Many Jōmon people had dental caries, which suggests a diet rich in starchy foods like acorns. Archaeological findings show large-scale acorn collection and stone tools used for grinding them.

In China, acorn remains have been found at several Paleolithic sites along the Yellow River, especially in the Loess Plateau. At Shizitan, dated to around 10,700–9,600 BCE, analysis of starch residues and wear patterns on grinding stones revealed that people processed acorns along with grass seeds and legumes.

In Southeast Asia, discoveries from Cai Beo in Vietnam show that people 7,000–6,000 years ago relied on acorns as a major food source alongside other plants such as taro and palms. This paints a picture of early hunter-gatherers using acorns before rice and millet agriculture took hold.

In Korea, acorns became especially important during the Neolithic Chulmun period. Analysis of stone-lined cooking pits shows that large quantities of acorns were systematically processed. This period also saw technological innovations in grinding tools, indicating that acorns were a central dietary component.

In Japan, acorns were also used as a survival food during the Edo period, particularly in remote mountain areas. During the difficult years during and after World War II, children were sent out to gather acorns, which became a necessary resource in times of food scarcity.

Europe

In Europe, acorns have been an important part of the human diet for thousands of years. Evidence of acorn use can be traced back to the Gravettian culture during the Paleolithic period—a culture also known for its impressive cave paintings and burial practices. A significant discovery was made in Grotta Paglicci in Puglia, southern Italy, where a 32,000-year-old stone tool—used as both mortar and grinder—was found to contain starch grains from wild oats and acorns. This provides the earliest documented evidence of food preparation in Europe.

In later periods, such as during the Ertebølle and Funnel Beaker cultures, acorns remained a staple food. Finds from the Neustadt area show that acorns were among the most commonly processed plants, with traces found in 90% of samples from these cultures. Acorns were typically boiled to remove toxic tannins, then ground into flour that nourished people during times of scarcity. In Denmark, archaeological evidence confirms this practice, with charred acorns and other plants like hazelnuts, apples, and barley found in the remains of burned Neolithic homes.

In Switzerland, at Bronze Age settlements, acorns were discovered alongside wild fruits and nuts such as hazelnuts and beechnuts, indicating their continued role in the diet across various historical periods. Even in the Linear Pottery Culture—one of Europe’s earliest farming societies—people still gathered and ate wild fruits and nuts, including acorns, despite cultivating cereals.

Throughout history, from Paleolithic foragers to Bronze Age farmers, acorns helped sustain human populations through difficult periods. Their rich nutritional profile has made them a vital part of traditional diets—and in some regions, they continue to play that role today.

North America

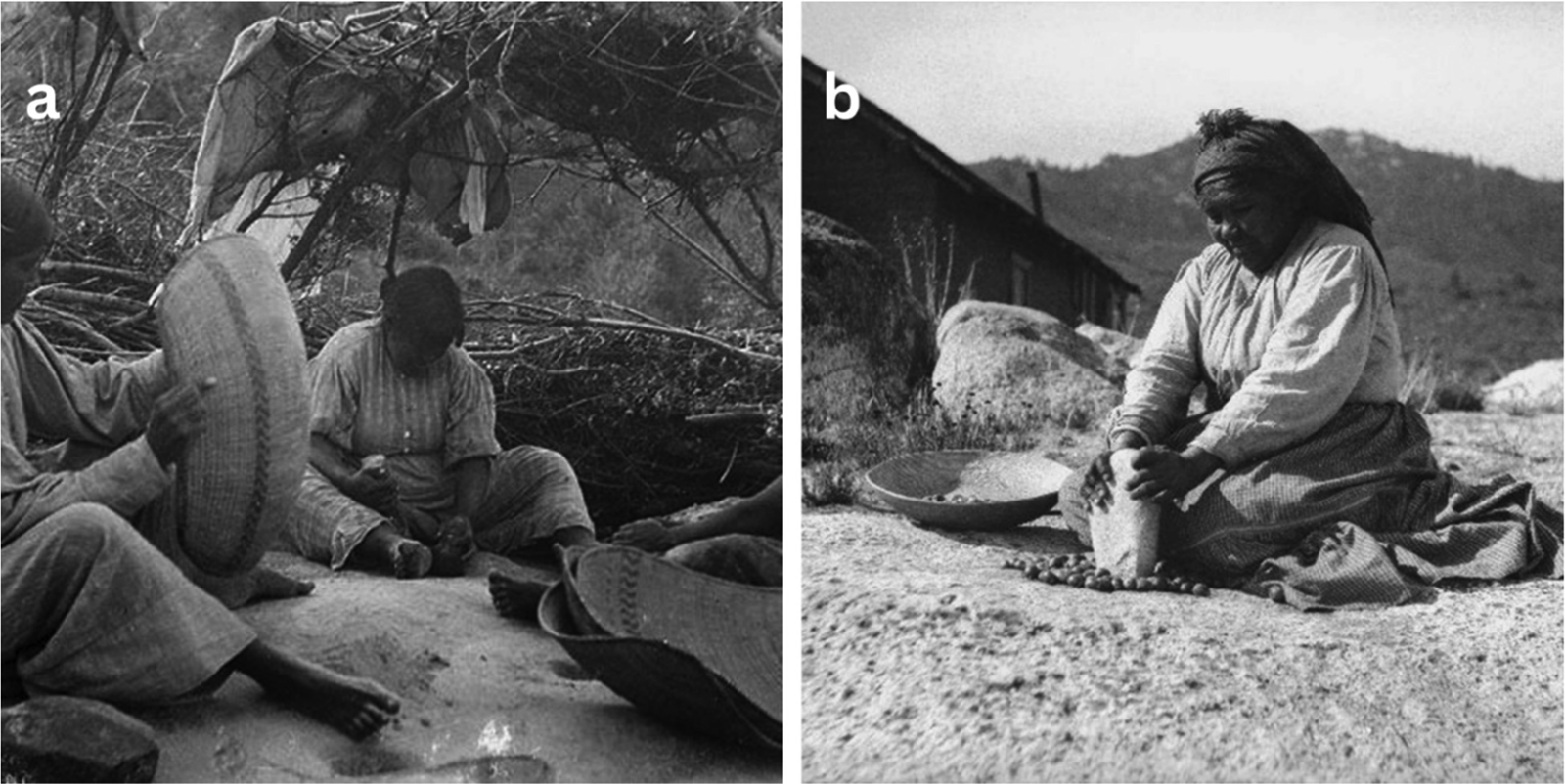

In California and southern Oregon, many Indigenous peoples—including the Salinan, Hupa, Yurok, Karuk, and Miwok—have long relied on oaks not only for food but also for cultural practices such as basketry and land stewardship. Acorns have served as both a staple food and a symbol of cultural identity for these communities.

Miwok women collected acorns in woven baskets carried on their backs, supported by a strap over the forehead. As with other groups such as the Pomo, acorn gathering was an important communal activity. Traditional knowledge about harvesting and processing acorns has been passed down through generations. But collecting was only the beginning—acorns needed to be processed to become edible. They were shelled, the kernels ground into flour, and the bitter tannins leached out using water. The resulting flour was used to make porridge, breads, and soups.

To grind the acorns, the Miwok used large stone slabs with bowl-shaped depressions—"grinding rocks"—that allowed them to efficiently process large amounts of acorns. One such site is now known as Grinding Rock State Historic Park in California, where mortars carved into bedrock remain as a testament to the central role of acorns in Miwok life.

For coastal peoples such as the Hupa and Yurok, acorns were also a dietary mainstay. They ground acorns into flour for porridge, bread, biscuits, and cakes—and they also roasted them for direct consumption. Oak trees and their acorns were indispensable, and the skills developed for acorn processing remain a key part of their cultural and physical survival.

Acorns were more than just food—they were a living symbol of history, knowledge, and a deep relationship with the land. Oaks, as a source of sustenance and a foundation for community traditions, have always been central to Miwok culture and beyond.

Among the coastal tribes, including the Hupa and Yurok, acorns were ground into flour and used in a variety of foods. The oak tree and its acorns formed an essential part of life for many of these tribes, and the knowledge and techniques developed for processing acorns continue to be an important part of their culture and survival.

Even today, as diseases threaten the survival of oak forests, more than just a food source is at risk—thousands of years of cultural traditions are in jeopardy for over 30 tribes collectively known as "The Acorn People."

The Decline and Rediscovery of Acorns as Food

With the rise of agriculture, acorns gradually lost their central role in many people’s diets, though they never disappeared entirely. Often considered famine food in times of hardship, they remained a fallback in regions where oak trees continued to thrive.

In recent years, acorns have been rediscovered—not just as a historical curiosity but as a nutritious and sustainable food source. This renewed interest is driven in part by a desire to reconnect with traditional foods and to seek natural, local alternatives to modern diets.

Acorns are particularly well-suited to current trends in foraging, local food sourcing, and gluten-free eating. The story of acorns as food is a powerful testament to human adaptability and ingenuity. From the earliest traces in the Hula Valley to today’s culinary experiments, acorns have nourished countless generations and continue to connect us to our ancestral roots.

Their enduring presence in cultures across the world shows just how important they have been—and still are—as a resource that has supported survival and shaped civilizations.